Racist Trees

Season 25 Episode 8 | 1h 23m 49sVideo has Audio Description

In Palm Springs, a Black neighborhood fights to remove a divisive wall of trees.

Were trees intentionally planted to exclude and segregate a Black neighborhood? Racial tensions ignite in this documentary, when a historically Black neighborhood in Palm Springs, California, fights to remove a towering wall of tamarisk trees. The trees form a barrier, believed by some to segregate the community, frustrating residents who regard them as an enduring symbol of racism.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Racist Trees

Season 25 Episode 8 | 1h 23m 49sVideo has Audio Description

Were trees intentionally planted to exclude and segregate a Black neighborhood? Racial tensions ignite in this documentary, when a historically Black neighborhood in Palm Springs, California, fights to remove a towering wall of tamarisk trees. The trees form a barrier, believed by some to segregate the community, frustrating residents who regard them as an enduring symbol of racism.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Independent Lens

Independent Lens is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

The Misunderstood Pain Behind Addiction

An interview with filmmaker Joanna Rudnick about making the animated short PBS documentary 'Brother' about her brother and his journey with addiction.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

A collection of films on African Americans.

Video has Closed Captions

The syncopated story of funk music, from its roots to the explosion of '70s urban funk and beyond. (1h 22m 7s)

Video has Audio Description

Father and son bond on an ambitious 350-mile bike ride in this portrait of familial love. (1h 24m 55s)

Video has Audio Description

The rich culinary tradition of soul food and its relevance to black cultural identity. (54m 8s)

Video has Audio Description

How Vegas activist Ruby Duncan's grassroots movement of moms fought for guaranteed income. (1h 24m 45s)

Video has Audio Description

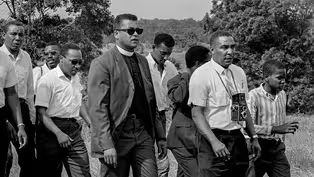

Meet Ernest Withers, iconic African American civil rights photographer—and FBI informant. (1h 25m 44s)

Video has Closed Captions

Hazing reveals the tradition of underground rituals that are abusive and sometimes deadly. (1h 43m 28s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ Narrator: On this golden wasteland, whose timeless tranquility offers rest, relaxation, men have built a village, which the world has come to look upon as the one resort in America which has everything.

♪ Tour guide: So, where are you guys from?

Woman: Um, Washington State.

Great.

Thank you.

Woman 2: I'm from Boise, Idaho.

Tour guide: Welcome.

Welcome to Palm Springs.

Tourism was the way this place actually started.

1850s, Europeans first really come here for the springs.

Narrator: Informal, warm, and friendly, Palm Springs offers accommodations to suit every person, every personality.

Tour guide: But really, the next big explosion is the film industry.

Narrator: Why is it that some resorts are mere vacation spots, but Palm Springs is an inspiration, a way of life?

Tour guide: This house here is the home of Debbie Reynolds.

That's where Elvis lived for a while with Priscilla.

Marilyn Monroe did rent this house.

She was, you know, the story is, "discovered" here in Palm Springs.

Narrator: And so they come, from all avenues of life.

Tour guide: Post this century is when everybody else, they see these midcentury modern homes.

Now it's become this very desirable place to be.

♪ [Birds chirping] Tour guide: Uh, questions?

Woman: Yeah, I have one.

Yes.

Just--'cause you mentioned there were some African-American architects.

And I was curious, like, back in the day, like, during that era, like, how integrated was the neighborhood?

Tour guide: There was definitely, uh-- a golf club here in Palm Springs that was exclusive, no Blacks, no Jews.

So, it--it was-- that was-- that's our history.

♪ ♪ Man: I'm gonna scoot you over just a hair that way.

OK.

There.

Let's try that.

OK. Sara: OK, hi, Charles.

Charles: Hello.

How you doing, Sara?

Sara: Good.

Can you tell me what it was like growing up here?

Charles: It was beautiful.

It was a neighborhood and community of where people could leave their doors open.

It was mostly families that migrated from Mississippi and Texas.

It was a village where we all looked out for one another.

And we called it the Crossley Tracts.

♪ All right.

Here we, uh... We have my parents, Jean Metcalf and Charles Metcalf.

Charles Sr.: We moved out here in '64 is when I bought the house.

But we came out here.

I got married out here, right there, in '63.

The trees was already here, but they weren't-- I always called it a shrub because they weren't that tall.

And, uh... they just-- they been here ever since.

Charles Jr.: As a kid growing up, they were just trees.

But as we got older, we started to understand why these trees were here and nowhere else.

They were planted to hide this community because of the people who lived here.

♪ Kevin: Look at Mama at 33.

Mom: Oh, that was-- ooh, wow.

Look at me, holding one of my babies.

Look at that one.

Mom: Was this yours, Kevin?

Kevin: That's my birthday.

Mom: Oh, yeah, everybody's around you.

Kevin: Yeah, I'm there.

Happy birthday.

Ray: And, see, that was-- that was my die hard right there, boy.

That Thunderbird.

Oh, my God.

In 1974, we bought our first house out here on Crossley.

Mom: Mm-hmm.

Kevin: That's right.

I wasn't born yet.

Mom: It was so nice, having your own place, you know, and having your boys have their own rooms, you know.

That was-- that was really nice.

Ray: We was glad to be able to buy a house for $18,500.

Kevin: Right, right, right.

[Laughs] And, um, the older generation, they took care of our kids when we wasn't here.

Callie: They watched out for them, you know?

Yeah.

Callie: All the kids would go on the golf course and play.

I could hear them playing out there, you know?

I remember playing on the golf course quite a bit when I was a kid, so... Kevin: I'm born and raised here.

I've been out here for 41 years.

We actually played in the trees.

And we got the golf balls out and sold them back to the golf course and to the golfers.

And it was-- those were the good ol' days.

Kevin: See all that trash and the dirt not kept up from the trees.

It actually takes about a good 10 feet to 15 feet of my yard that I can't do nothing with.

I used to have an above-ground pool in here, but the needles would blow so much, I couldn't maintain it, so I took it-- took the pool out.

My kids can't play back here.

My kids can't swing back here!

Who's supposed to maintain this?

Not I. I raked it up yesterday-- the day before yesterday, I raked it up.

And they're nasty.

And they're nasty.

And they're nasty.

Charles: This is what you get.

You get a buildup.

It's just a habitat for a lot of unwanted creatures.

Rats, rodents, snakes.

I can't cut the trees because it's not my property.

But the city claims that they maintain these trees, which you clearly see that these trees are not maintained.

Because you don't grow this in a matter of months.

This grows over a matter of years.

Like, I feel segregated from it.

I feel like I'm not a part of Palm Springs with that golf course and with those trees up.

I feel like, Why am I not on a golf-course view?

Why is my property value not going up gradually?

What's going on?

Well, they wanna keep you down.

They wanna keep you there.

But Palm Springs is growing and now we're-- we wanna be part of the community.

♪ ♪ Trae: I lived here in the neighborhood for several years without noticing, without paying attention, without having what is called awareness, awareness of the trees.

They're just there.

When I arrived here in 2003, the neighborhood was predominantly Black.

I don't think there were any Whites living in the neighborhood at that time.

I came to this particular house because I was looking for a property in a particular price range.

The realtor said, "I don't think the area is very good."

I said, "That's fine.

Let's go look at it anyway."

So, we're driving down the side of the golf course.

And I'm thinking, "Wow.

This looks really nice to me."

And then you pass this wall of trees, you're in an entirely different world.

The neighborhood had a very rough reputation.

You would call it depressed or marginal.

But, uh, here was a brand-new house at a price I could afford.

♪ Trae: Mr. Crossley incorporated this as a subdivision to provide housing for the Black community, who had no place to live.

Charles: Domestic workers, who were Black, see, they--they can come in and be domestic workers in the city, but you just can't live in the city.

Trae: Even the entertainers who came to Palm Springs were not permitted to stay at hotels or residences in Palm Springs.

Trae: Palm Springs is no different from any other community in the United States.

There has been research done that shows the wealth gap that exists between Blacks and Whites is the result of accumulated wealth.

Accumulated wealth comes from inheritance.

Inheritance comes, many times, from property, from real estate and property values.

And the Black community has not been able to accumulate wealth.

So, the injustice is keeping these trees here, knowing that, you know, it's devaluing our property.

Real estate has exploded in Palm Springs.

The average price of a house in Palm Springs is $575,000.

The average price of a lot is probably $200,000.

You can't get $150,000 for the lot and the house here.

Why?

Simply because those trees are there.

When we tried to get the city to remove them, they say, "Oh, it's on Edison," you know?

Or it's on the gas company.

And then each one is not taking responsibility.

So, that's the red tape, that's the stonewalling, that's the runaround that we get.

Because they say, "It ain't me, it's them."

And then you go to them, they say, Well, it ain't them.

"It's them."

And, you know, but the fact of the matter is, the city of Palm Springs planted these weeds.

♪ Sara: Um, is it comfortable to sit like that?

J.R.: I can sit any way you want.

I just had a pedicure, so I'm OK with them showing.

[Sara laughs] Palm springs, of all cities now, is like Berkeley.

It's so diverse.

It's so open to everyone and everything.

We're so progressive, we're so liberal, that accusing Palm Springs of being racist now is almost ridiculous to me because we just don't see it.

Nobody at City Hall is convinced at all that this is a racist issue or ever was a racist issue, not that we didn't have those issues.

We did in a big way.

But these trees in particular?

Nah.

Mayor: OK, any other items?

Ginny: We wanted to ask about the tamarisk trees, uh, and--and who has made the suggestion that those trees were going to be cut?

David: So, so let me clarify.

For all of a sudden, there seems to be a lot and-- Ginny: We're getting a lot of mail on this.

David: Two things.

we're doing nothing until everyone's happy and clear of what we're doing.

And it's gonna require, if we did any significant action, surveys of the neighborhood, et cetera, et cetera.

Ginny: But how did this start, is--is what-- David: I do not know.

Marcus, perhaps you have a little more insight?

Marcus: I mean, it's my understanding they were there to, uh, protect the homes there from errant golf balls, 'cause they're right at the end of the fairway.

J.R.: But--but do they-- other than the use of water, do they have any other negative impact?

Marcus: Uh, not that I'm aware of.

J.R.: I'll be anxious to hear your outcome on that.

But the rumor mill is churning.

And we're getting a lot-- we're getting a lot of mail on both sides.

♪ ♪ Trae: Look, it's about discrimination.

I hate to--I hate to put it in racial terms, but that's what this is all about.

If this had been a Caucasian community from to begin with, there would be no issue here.

J.R.: Racial motivation can get things done.

It wakes people up.

It can shame people, and it can get things done.

It doesn't mean it's always true.

Marcus: The only thing that we had talked about doing was doing some trimming of the lower parts of it and cleaning up the debris at the bottom, uh, near the fence line.

But we haven't proceeded with, uh, either.

J.R.: If you're looking for a pristine White community, like, or conservative, we're not that community.

There are other cities down valley that fit that image better, but it's not us.

Kevin Williams: We just want what everyone else has in this neighborhood of Palm Springs.

We want to not be known as the neighborhood-- Black neighborhood over there in the corner that has trees and you don't even see us over there.

They've been staring at a wall.

What's the difference between that wall and the Berlin Wall?

They say that these trees are not racially motivated, that they were not racially planted there.

They can prove that by one simple act.

Remove the trees.

♪ [Birds tweeting] ♪ Trae: Good evening.

I'm Trae Daniel, and I live in the Crossley Tract.

This is the piece of land that was owned by and lived on by the African-American Palm Springs pioneer Lawrence Crossley.

I'm here to say that Black Lives Matter, that Black history matters, and the Black lives and Black history of Palm Springs in particular matters.

Corinne: Trae has kind of become, like, the community organizer for the Crossley neighborhood, and was really the one behind this drive, who brought it to my editor's attention and then mine.

And so, I asked to come out and see the neighborhood.

Trae was very prepared.

I think he had about a 12-inch stack of documents that he shared with me-- city meetings in the '60s and how the neighborhood was established.

Just about the history of racial issues in Palm Springs that I didn't know a lot about.

At the time, African Americans were not allowed to live inside Palm Springs proper.

A wealthy African-American man by the name of Lawrence Crossley bought this tract of land and developed it as a place for Black families.

Corinne: Having that historical context with this visual representation, that's when I started to realize there's something here.

Jarvis: Lawrence Crossley, he was a true pioneer.

He came to Palm Springs for a better life for his family, just like anyone else when they left down South to come west.

They came for a better life.

And when he came here, he made some great power moves.

Jarvis: He actually came from Louisiana in the 1920s.

And, uh, he was a chauffeur to a great businessman in Palm Springs, Prescott Stevens.

Lawrence was able to start businesses.

He was an entrepreneur.

He helped design the first golf course.

He was part owner of the Whitewater Mutual Water Company that was built here in Palm Springs.

He had a tea/coffee company where he was able to sell a special herbal tea that he had got from local Native Americans.

And his tea sold all the way across the country.

And he welcomed families to live on land that he was able to get.

Now, in 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, that wasn't normal for minorities to actually own land.

A lot of folks were able to buy homes there in his property, start families, and begin a whole new lifestyle.

And nobody else in Palm Springs would do that for African Americans due to Blacks not being allowed to purchase land or even secure a home loan.

But Lawrence made it possible.

A lot of people still don't even know this neighborhood is here.

They still don't know about Mr. Crossley.

Delivery guys will come in here, say, "Huh.

I didn't even know this was back here," you know?

Rosie: I've been here in Palm Springs all my life.

We had moved from, uh, Ramon Trailer Park when I was, like, four years old.

Rosie: Mother and Dad knew Mr. Crossley, and I always heard how wonderful of a man he was.

And if Mother needed something, she would ask him or she'd talk to him, and he'd give her advice, and he was just, uh, he was just a very good person.

He must've been the kind of man that wanted to see life work.

Rosie: For everyone.

He wanted things to progress.

He wanted to see people do well, people upgrade their standards.

He was that kind of a guy.

Kevin Harmon: And then the trees were a block that kept people from actually even knowing this neighborhood was here.

Corinne: I started doing my own digging through city archives, historical society archives, the newspaper's archives.

There wasn't a lot of documentation about the trees, specifically.

There was a lot about Lawrence Crossley.

Um, and there was a decent amount about kind of him building this neighborhood.

At the same time, a golf course was being developed right next to this tract.

And it's unclear exactly why or exactly when, but at some point, a row of trees went in.

Corinne: So, it was kind of a lot of pulling together the documentation that was available with interviews with everyone who had a stake in the issue and kind of trying to piece together from all these very different accountings of the issue, kind of what might be going on.

Angie: My name is Angie Johnson.

I work in the conservation industry, and I'm an ISA-certified arborist.

This is not a tree I would particularly plant in my own yard.

It is dirty.

You get a lot of dead within because you're only getting photosynthesis on the outsides.

They do take copious amounts of water, upwards of 300 gallons a day per plant, so that is very damaging on our aquifer.

You know, I mean, it's even a fire hazard when you think about it.

So, there's a lot of reasons I personally would not want this.

And they're very invasive, so they're gonna start sprouting throughout the yard, and it's gonna make it difficult to have other plant material.

Angie: These are not a native plant.

They were brought over to North America in the 1800s from Asia and West Africa.

It was sold as a landscape ornamental plant.

And then they really started promoting them for windbreaks.

And out here, especially in this area, we get massive sandstorms.

So, now basically, you'll see them along the railroads or near any developments that have sand on the other side.

That is really the most common.

♪ Kevin Williams: So, how was it when you guys-- Callie: When we first moved here?

when you guys first moved here, about getting the trees out, and how was the neighborhood and-- Well, it first started off as we're trying to get lights and sidewalks, you know... Kevin Williams: And sewer.

Ray: And sewer.

And sewer and all that.

Callie: And then we didn't get it.

There were no streetlights, no curbs.

Kevin Williams: No streetlights and no curbs.

Yeah, I see.

Callie: Dirt roads.

Dirt roads, yeah.

It was ugly.

Here's a picture when we got flooded.

Oh, wow.

Ray: By not having no curbs, Kevin, Palm Springs didn't have the drain system turned away from the neighborhood, so the water came through the dream homes, and this is where it stopped.

Callie: The water was, like, three feet high in the house.

Ray: Mm-hmm.

Kevin Harmon: This neighborhood didn't get any city services.

And so, the people that lived here had to clear the streets when the sand blew.

They just--there were no street lights.

There were no sidewalks.

Sidewalks didn't get here until when?

Pretty late.

There might've been an argument over whether this was Cathedral City or Palm Springs.

Once the lines became defined, it still didn't get the services that were necessary for this neighborhood.

Trae: In the '90s, the city erected a six-foot chain-link fence between the Black property owners and the golf course.

Not the White owners, just the Blacks.

Charles: And one year what the city did was they came in, and they trimmed up the trees on the property side so that they could put this chain-link fence in between the property and the golf course to try to keep people from, you know, going to the golf course.

So, not only did they plant the trees, but they put this fence here.

Kevin Williams: I used to be able to walk through the trees and play on the golf course.

What happened?

Why-- why this fence went up?

Why is a little kid that couldn't go out there anymore?

It all started from me telling Trae, and Trae was a voice for us, to be able to speak and say, This is what's going on.

This is what has been going on.

Kevin Williams: I purchased my house in 2010.

And when they'd cut the tamarisk trees, the tamarisk tree would just fall in my backyard and damage stuff.

So, as time went on, and I started to complain a little bit more.

I wrote emails to the golf course, CC-ing the city of Palm Springs.

You know, no one ever said, "Mr. Williams, you know, what can we do for you?

What's gonna happen..." none of that stuff.

And as I met Trae, we talked about those things in the meetings about what would we want for our neighborhood.

Kevin Harmon: Most of the Lawrence Street people were there, but they were resistant because Trae's a White guy.

Ha ha.

And he's trying to explain, we need to get the trees out.

And everybody said, "Well, I don't know."

And he said, "We need to organize "and form a community group to have some political sway at City Hall."

And then I stood up and I said, "I think that's a great idea."

I said, "That's... we have to do that."

So, Trae was like, "A Black guy on my side?"

It was kinda nice.

And then we formed the community group.

Trae: I'm talking about property values here.

I'm not just talking about racial issues.

I'm talking about property values.

That's the issue.

Man: That's what I-- I didn't bring that up.

I mean, I tried to bring the issue up about those trees in 2004.

Yeah.

Man 2: Let me show you something... Trae: Yeah, Hank, what do you got?

Clem?

[Indistinct conversations] I talked to an arborist.

He said there was a good chance they could be cut down to about 10 feet, 12 feet, and made into a hedge like that.

Then you have a view of the mountains.

Trae: No.

Let me tell you why.

Who's to define what maintaining those trees is?

And, let me finish.

Now--OK.

This isn't your battle.

You're not in our neighborhood.

OK, well, I'll go home.

No, I want you to stay.

And then what happens five years from now and they don't want to maintain those trees anymore?

Janel, voice-over: Trae Daniels had reached out to the Palm Springs Black History Committee and was looking for people to speak up about the trees.

I thought it was just strange.

Um, I am a very skeptical person.

[Laughs] Um, we had never seen Trae before or heard of him.

Trae: He is not in our neighborhood.

Now, if nobody here wants your property values to go up, fine.

Leave 'em in.

Kevin Williams: Right, right, right.

No, we want 'em out.

We want them out.

Janel, voice-over: From my understanding, he doesn't even live on Lawrence Street.

But I think the trees were a nuisance to him because you-- you couldn't even see.

You couldn't see the mountains.

And I think he was trying to get as many Black voices as possible and allies to say, "Hey, this is an issue."

So, me being an activist and sitting on the Palm Springs Black History Committee, we wrote letters and we would go down to City Hall meetings and, um, speak up on the topic.

Couldn't get much of a response from the city people.

I mean, it wasn't the first time that the topic of the trees was brought to their attention.

The can has certainly been kicked before.

So, what Trae has done is-- is not something new.

But the city just turned a deaf ear to us.

♪ Corinne: Palm Springs is, to some extent, a kind of a segregated city.

There's the more affluent White neighborhoods, and then there's the Black neighborhoods.

The Lawrence Crossley neighborhood, it's still predominantly African American, but there are White people who have moved into the neighborhood.

There are some Latinos.

So, it is--actually, it might be the most diverse neighborhood in Palm Springs.

Corinne: It wasn't always kind of this liberal progressive utopia that people see Palm Springs as now.

Kurt: My partner Jay and I purchased this lot about three years ago in hopes of building our dream home here in Palm Springs.

Cathie: My son has lived down here for six years.

And we visited him, and I said to my husband, "You know, I could see myself living down here."

And he says, "I don't think so."

Well, here we are.

Our association with the tamarisk trees are fairly new, though I am aware of several neighbors who have worked very diligently in their removal.

And we support them wholeheartedly.

I've never seen 'em, but apparently there are, uh, packrats or whatever they call 'em.

And we do have little cottontail bunnies that I know live in there.

I just want 'em out because of the nuisance, and, plus, I wanna have the million-dollar view like other people.

Sara: So, do you believe what--initially, when they were planted, that the intention behind that was to discriminate?

I can't get into, um, the mind of those people.

But I think circumstantial evidence proves that point.

Back in the '50s, I can see that happening, 'cause they more or less just thought that the Blacks were supposed to, you know, do work as maids and cooks.

And, you know, but, like, they-- they were discriminated against.

Corinne: In the course of reporting, I talked to White and Black residents of the neighborhood.

They both said, like, "No, I think there was racial motivation here."

And whether they really believed that or they just thought it was a compelling argument, I don't know.

But the vast majority of residents that I talked to did say they thought race played some factor in either the planting of the trees or the not cutting them down.

Donald: So, you can see from here over, I just keep this constantly, you know, clipped back, so they--they don't cause any issue for us.

If you, you know, take care of 'em, they're just fine.

And the birds.

You know, you should see all the birds we have here.

Trae: One resident likes the trees.

With all due respect, he is White.

What his rationale is I don't know.

I would say to him this... [Laughs] When those trees come down, if you're bothered by the golf balls and you don't want to live there anymore, you can probably put your house on the market and make a $50,000 to $100,000 profit and move on.

Donald: Trae came to the door and was kinda taken back by that I actually liked them.

Really green and shady, and, you know, it was gorgeous.

It's really good for my husband--Robert.

He's got issues about safety from his service in Afghanistan and Iraq.

And so, when he walked back here, that's one of the first things that he felt, was the safety of the trees.

I just can't see a tree being racist.

Yes, that could've been somewhat of a issue, but why do we have to pay for that today?

Trae wasn't here when those trees were planted, so he doesn't have a clue why they were planted.

So, the city doesn't really know the history either, so everybody's guessing.

Charles: There's no tamarisk trees anywhere else along this golf course anywhere.

Now, I'm not blaming the current city officials for planting these trees here, but I'm kind of borderline blaming them for being the reason why they still here.

J.R.: Remember, we're gay.

We have been-- [Laughs] I grew up in an environment of-- of anger and ugliness and hate and hatred, too.

I know what that feels like.

I had to hide who I was my whole life.

I had to deal-- and all of us had to.

So, it's not anything we shy away from.

It's something we probably understand better than most and we're probably more sympathetic to.

I've--I've lived with discrimination, also.

I'm gay, so I-- I think that that's a really weak argument.

I really do not think that this was ever a issue before Trae.

Corinne: I don't know exactly why Trae is so invested.

But obviously, this impacts him personally, 'cause he is a resident there and the--the trees would affect his property value.

He's also a real estate agent.

Um, some--like, some people I've talked to have suggested that he wants the trees removed so that he can flip-- flip the houses and kind of gentrify the neighborhood and make a lot of money in the process.

You'd have to ask Trae.

Um, it's certainly possible.

You realize he benefits directly, right?

All those real estate values will definitely jump up.

To have the guy who benefits directly financially come forward on an issue always puts a little bit of question in it for me.

Why is everyone so concerned about what is in it for you?

Don't you just do something because you care about somebody else?

Trae: Everything that anyone does that comes from love is life enhancing.

Somebody who says, "What's in it for you?"

is coming from fear.

♪ ♪ Corinne: The first article I published about the trees got a lot of reaction.

[Social media notification chime] Corinne: But then it got picked up, I believe, by The "New York Times," "Politico," and then it actually made it international, too.

There were stories in the UK "Daily Mail" and the "Guardian."

After that, it kind of made it into Breitbart.

And then, I'm not sure if you're familiar with 4chan and some alt-right channels.

Male YouTuber: I brought my viewers to hell because that's what these trees exemplify, is the nastiness of the universe.

They belong in a fiery pit to burn forever.

Different male YouTuber: Talk about a conspiracy theory.

I mean, it's like, if-- if nothing else works, you throw out the abortion card, you throw out the racist card.

First male YouTuber: Yes, I'm talking to you, trees.

You trees are racist.

What do you have to say for yourself?

What do you have to say for yourself?

What?

Corinne: There were a lot of people who attacked me as a way of attacking the story.

Um, some really vicious things, but... [Chime sound] Trae: I think that article got a lot of people's attention because now not only is the city aware that there's a problem here, but residents of the city are aware.

You know, it's always all about creating awareness.

Corinne: On the day it was published, I see I have a missed call and a voicemail from the city manager, and I was just like, "Oh, no."

He just said, "You know, we all read your story, "and I want you to know that, like, "we're scheduling a meeting with some of the residents to talk about this issue."

The City Council that we have in place today in the city of Palm Springs is not truly a representation of all the people.

It doesn't include anyone that looks like me, that I may share the same culture with.

Janel: So, when the newspaper hit about those racist trees, I was like, "Hell, yeah.

"Let's talk about what is going on in the city of Palm Springs."

Corinne: The city has an annual budget of, I believe, 110 million or 112 million, which is very large for a city of 45,000 permanent residents.

I'm sure they can come up with the money somewhere.

I guess the question is, Just how much of a priority is this for the city?

Trae: Good to see you...

Rob, good to see you.

-Good to see you again.

-Hi, David.

-Kurt.

-Hi, Kurt.

J.R.: Don't you know we're the gayest city council in the United States?

What about Christy?

What about her?

Is she gay?

Is she?

I was just curious.

I don't care one way or the other.

Yeah, she's the B of the LBGT, yeah, Q.

We don't have a Q.

No.

But we have an L, G, and a B and-- Trae: As you are guests in our neighborhood, would you like to make opening remarks first, or...?

J.R.: Yeah, yeah.

Trae: OK. David: The key thing here, I believe, and I'll let the subcommittee speak, but we need to hear from you, what we really wanna talk about, the people that actually live on this street, um, do you want the trees removed?

Robert: Whatever we do will cost a certain amount of money, and so, what the mayor pro tem and I can do is be here and listen.

And then we'll make our-- we'll report back to the full council.

But it will require a vote of the full council to take any action, and will cost any funds from the city.

J.R.: Taking out the trees and taking out the chain-link fence is gonna cost about $200,000 that we're not budgeted for.

I think that's a small price to pay.

And I think the city can put that in their budget to have these trees removed.

Trae: I wanna make some comments on behalf of the neighborhood because this is-- I'm the one that started all this.

First, you're concerned about funding.

Southern California Edison, they're spending probably $10,000 or $20,000 a year to cut those trees to keep them from interfering with the power lines.

Why don't you contact Southern California Edison and ask them for half the price of removing the trees?

J.R.: Well, can I respond to that?

Trae: No.

I'd like to get all my points out first.

And then we can have-- and then I'm gonna turn it over.

Let's go piece by piece, OK?

[People speaking at once] Guys, guys, listen.

Guys, guys... Man: He listened to you guys.

Let's deal with each issue.

Let's make it clear.

These trees were not put here because of the golf ball issue.

We all know why these trees were put here.

Official: OK.

So, I'm glad to see you-- the city here and willing to remove 'em.

Just quickly, How many want them out?

Raise your hand.

-By the root.

-By the root.

Man: By the roots.

Female: Yep.

Male: All the way out.

Male: Not only here, but on the back street over here, also.

J.R.: We should take them out.

OK.

Female: Yes.

Yes.

By the roots.

J.R.: And who wants them to stay for any reason?

Just one, one guy?

Donald: Just walking down the street here to--back to my place, two of them I found in my front yard.

Man: Right.

So, it's like, this-- there's a reason that they're there.

Ha ha.

[Residents speaking at once] J.R.: Guys, guys, guys, can we all stay-- can we all stay as a group?

Man: And we want to know exactly how we can make this relevant to the city of Palm Springs.

'Cause I feel like that we're the last of the last to be talked to or even be treated right here.

We still have these old electric poles.

Whatever happened in the past may-- may not have been right, and there are lots of examples of that all over the city.

And the city is just a city made up of people.

Man: We're gonna make it right.

Mistakes were made.

Things drop through.

Economies change.

We're here.

We are committing to you to solve these problems.

I will tell you this, you're not the only neighborhood that has problems and things that need to be fixed.

Male: I don't care about nobody else's neighborhood.

I care about this neighborhood right here.

We're going neighborhood to neighborhood.

But guess what.

The loud ones get our attention.

And so, we're here.

Charles: We can't get much louder.

You can't get much louder.

Kevin Williams: And now that we have a community, our Crossley Tract community, we're gonna-- our voice is heard.

J.R.: And by the way, that changed everything.

Charles, voice-over: They knew that they were being watched.

They knew that--you know, you had your camera crew out there and so they're on camera.

They know that these things are being written about and reported.

So, I believe that on one hand, they said what they had to say to the residents.

Jarvis: Nothing could happen until there was a White man.

Heh.

A White man came to City Council and said, "Hey, I have a home here, and I don't like these trees."

But because he said something, now the city wants to listen.

Janel: He has White privilege, and he used his privilege because the residents of Lawrence Crossley had been fighting that battle for way too long, and still couldn't get that same reaction that he did.

Charles: When they're sitting across from Trae, they're looking at one of their own, you know, instead of looking at somebody, say, like me.

Because the city don't see us as human beings.

They don't see us as people.

They see us as Black people.

Kevin Williams: I don't wanna look it as Trae, that White man or that Black guy.

I wanna look at is as, "Hey, you know what?

We're a community now.

We want change."

And we have a spokesman that's gonna help us get to where we wanna get 'cause he's a caring man.

He doesn't even live on this side of the block, but he understands our hearts.

When he understands our hearts, that's when things change.

I think the city just wants this over with.

I don't think they want to prolong it.

Listen, we live in a virtual reality world.

Everything goes viral the minute it comes out.

Everybody everywhere knows what's going on.

So, people are aware that there's a problem here.

I think the city just wants it done, over with, and out of the way.

♪ Tucker Carlson: Can you tell us how you reached this conclusion?

What racist sentiments have they expressed to you?

Um, how can you prove these trees are racist?

Uh, these trees, Tucker, are not racist.

You're the one that said they were racist.

Oh, OK. OK. A tree is neutral.

It's benign.

All right.

And it's not the tree, it is the individuals and their intent when that particular type of tree was planted in that particular location back in 1958, '59, '60, '61.

Tucker: Right.

Trae: And if you've done any research on the tree, you'll know that's one of the nastiest trees around.

And it's also been declared an environmental disaster by the federal government... Tucker: What?!

They grow to be 60 feet tall and they grow to be 25 feet wide.

Wait.

No, slow down.

Well, hold on.

Because that tree is a foreign tree, you're calling it nasty?

Trae: Correct.

Absolutely.

Tucker: OK.

I guess the California I grew up in was a little bit more welcoming to foreigners.

[Chiming sounds] Man: Liberals have run out of racist statues to take down, so they've now moved on to racist trees.

Man: I don't know.

I would like to think that nothing's racist... Tucker: I would, too, but, uh, my eyes are open now.

Larry: Go figure.

It's all about making Black people feel better about the past, about Jim Crow, about slavery, as if that's the issue facing Black America.

Andre: In many cities, there's a line of demarcation that separates those who "belong" and those who do not.

It can be trees.

It could be a railroad.

It can be a street.

While certainly inanimate objects should not take on human characteristics, they do represent the racism of people.

Black neighborhoods didn't evolve out of, you know, nothingness.

They have a policy context.

I'm Andre Perry.

I'm a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, where I study the assets in Black-majority cities and neighborhoods.

And we know from the research that we've done that in many cities, including Palm Springs, that many assets are devalued.

And what we found after controlling for education, crime, walkability, all those fancy Zillow metrics-- that homes in Black neighborhoods are underpriced by a significant amount.

♪ ♪ Andre: Median wealth for White families is about 170,000 compared to about 17,000 for Black families.

If the homes in Palm Springs were priced what they are actually worth, you would see more revenue for communities, more revenue for families.

Resident: Come on.

Come on.

Andre: It is great when people rise up and say, "You know what?

Enough is enough."

We've grown to live with these trees in the same way we've grown to live with discrimination.

Andre: The reason why so many White people have wealth is not because of their financial literacy or their savvy.

It's because the federal government supported them, invested in White communities during a very vulnerable time in this country.

And that action led to multiple generations of Black people not having the same ability to accumulate wealth as their White counterparts.

But it was this overarching framework that stated that Black communities are not worthy of investment, that they're hazardous, that they're dangerous, and therefore, they don't deserve federal, state, and local support.

Andre: And so, these trees are just symbolic of the walls we put up to deny Black people the opportunities to be Americans.

[Indistinct conversations] Andre: But when things go wrong in Black communities, we blame Black people.

We don't acknowledge the policies that created these environments.

Now, you can be a progressive town and still hold on to racist traditions.

♪ Corinne: Well, across the 14th fairway from the Lawrence Crossley neighborhood is a condo complex called Mountain Shadows.

And I got a lot of calls and emails from people saying, "We live right across the golf course from these trees.

We have a stake in this."

And they were really upset that they had never been consulted about that, which I think is fair.

♪ ♪ Corinne: So, I went out to the condo complex and met with a large group of residents.

And so, some felt that they were being painted as racists, and they were like, "You know what?

This is really unfair.

You called me a racist in the newspaper."

♪ ♪ Mayor: This time has been set aside for members of the public to address the city council only on agenda items.

And each person will have two minutes to speak.

Resident: I've lived in the Mountain Shadows complex in Palm Springs for the past 35 years.

I bought my unit because of those trees.

They gave me some solitude and some quietness and some atmosphere.

And I don't see any reason why we should cut down something that's living and green and beautification to the neighborhood.

Those trees are a hazard.

They catch fire on a regular basis.

And they're an invasive species to our desert.

I have lived on this property for nine-plus years.

I have never seen a fire.

Yes, I have rats.

It's my turn to talk, not you.

The trees, they are a health hazard, and they're rodent-infested, OK?

So, if you're not gonna take 'em down, at least clean 'em up.

Kevin Harmon: The people in the Mountain Shadows condominium project, there are about 250 units there.

Only 25 of those units actually face-- the tamarisk trees.

So, it's a simple matter of fairness.

It certainly speaks ill of Palm Springs to leave the trees there.

Thank you.

[Applause] Narrator: Isn't this a sight?

In the middle of all this desert, an oasis.

This is Palm Canyon on the Agua Caliente Indian Reservation.

♪ Just down the hill from the Indian reservation is another, perhaps better-known oasis, Palm Springs, with 360 days of sunlight and a warm, dry climate that always picks up my spirits.

♪ Tyrone: When most people think of Palm Springs, they're thinking of a getaway.

But the getaway is different depending on who you are.

If you visit Palm Springs as a person of color, you might not see people who look like you everywhere you go in the restaurants and in the hotels and at pool sides.

Tyrone: This state has this air of possibility, right?

And there's an openness and a diversity to it.

But all those things have come at a great cost to those who were once excluded.

My name is Tyrone Beason.

I'm a reporter at the "Los Angeles Times."

And I write about politics, but I also write about things that are highly politicized.

And, of course, at this moment in the country's history, race and identity is such a huge part of that.

Palm Springs has this story, too, and it's sort of under-told.

Narrator: Long before it became Palm Springs, California, desert playground of millionaires, this bit of real estate was an Indian reservation, as poor and as desolate as any.

Unlike other reservations, however, this one was laid out like a checkerboard.

Renee: Many people do not know that Palm Springs is Tribal land.

But the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians go back almost 5,000 years, and possibly more than that.

The hot water spring that actually made Palm Springs, that was the center of their spiritual and their cultural lives.

And they believed that that water was healing.

Narrator: Not until the 1880s, however, was Palm Springs able to attract permanent settlers.

Renee: During the Depression in the 1930s, one of the industries that was making money was movies.

So, the movie industry came here, where they could be a Western town or they could be the Sahara Desert.

♪ Renee: Frank Sinatra, the whole Rat Pack, Dean Martin had a house in Las Palmas.

Elizabeth Taylor.

And, I mean, the names just go on and on and on.

But there were always a lot of jobs, and that's what brought the Black community.

Tyrone: We think a lot about the Black migration being from south to north.

You know, from the delta of Mississippi to Harlem, Chicago, Detroit.

So many Black people moved west, actually.

They made this incredible 2,000-mile journey to the West Coast in search of the same things that brought White people here, to be honest: opportunity, a sense of openness, a place to put down roots.

Woman: I think the middle-class negro is striving to give his child what he did not have.

Man: I assume that he would wanna live in a White neighborhood or any other neighborhood because he's supposed to be an American citizen.

We have gone so far being poor.

And finally, when you get this chance, you think that you have made it into America, the American society.

Janel: People always ask, like, "How did you end up in Palm Springs?"

My family has been here since 1944.

My grandmother is Claudy V. Crawford.

She came by way of-- she had an older sister-- Donetha Thomas, um, who came out here because her husband was in the military.

Basically told her, "Hey, come on out "to Palm Springs, California.

You know, there's work out here."

Jarvis: A lot of the families came by word of mouth when they were hearing from other family members, saying, "Hey, come on down here to Palm Springs.

They got work out here for you."

Most of those jobs were working in the homes of some of the affluent folks of Palm Springs.

And some of them did landscaping or construction or whatever it was.

When they came here, they wanted to see something better in life.

Tyrone: For years, many people of color in Palm Springs-- Black people, Mexicans, Native Americans-- lived on reservation land called Section 14.

And it was an area that many people outside of those boundaries thought of as a slum.

They weren't really looking to live in Section 14.

But because of housing covenants and other restrictions, written and unwritten, from Palm Springs out to Indio-- throughout the Coachella Valley, actually-- it was really impossible for Black people to pick and choose where they wanted to live.

[Indistinct conversation] Mildred: Ever since I can remember, there's always been Blacks, there's always been Mexicans, there's always been Filipinos.

We were friends with everybody.

We didn't consider ourselves, um, poor or-- or, uh, neglected or-- nobody had anything, so it was no difference.

We were all the same.

They called us "land rich and money poor" because we had the land.

We had the majority of the land in Palm Springs, the city of Palm Springs.

Through the '40s and '50s and '60s, city fathers kept a very tight thumbscrew zoning effect on the Indian land, so we could not develop our land.

Janel: Growing up, my granny, she would share a lot of stories about her time on Section 14.

She used to talk about how the houses were basically, they were makeshift houses.

Jarvis: I got most of my stories from our grandmother, Cora Crawford.

And she would tell me they'd had to go to family members' or friends' homes to utilize running water because there were no city services.

But, um, I do have family that's still alive who actually lived on Section 14 as a kid.

And, um, I'd like to introduce him now.

Uncle Abdullah, come on through.

Abdullah: Thank you.

Abdullah, voice-over: I came to Palm Springs in 1947.

We lived on the Section 14, the reservation, as we call it.

And, uh, we stayed with my aunt, my father's sister.

She had a nice house.

And, uh, life was good, as far as I was as a little kid.

I didn't recognize a lot of stuff until later on in my life that was difficult.

Abdullah: Well, over the years, there were rumors that we were gonna have to move off of Section 14.

Then that was sort of spooky to me because I had just got married, I was young.

And that was sort of spooky to me.

I had a wife and a little baby.

And I says, "Oh, gee, I'm gonna have to move here, maybe."

And so, some people came home to see-- where their homes were just gone.

♪ ♪ Janel: Frank Bogert, at the time, who was the mayor, along with some city council members, they discussed a way to come up with some negotiations that would then prevent people that lived in Section 14 from being there.

Some people did not have any notices and--would leave to go to work, come back and find their houses in--in shambles, you know, nothing standing.

Charles: I've heard my great-uncle speak about it.

I've heard other elders and other people speak about that.

From what I understand is that one day they came in and they bulldozed down everybody's homes while they were out working and set the piles on fire... and pushed everybody out.

♪ ♪ Tyrone: It's not just the burning of the buildings.

It's not just the--the bulldozers.

It's the idea of your own town turning its back on you.

It's the idea of America turning its back on you once again.

Remember, these are people, in many cases, who escaped the South.

And this is what they got.

Narrator: In the early '30s, its climatic and topographical charms were discovered.

And today, fashionable hotels, apartments, and clubs with sweeping lawns and lovely gardens have taken over.

Palm Springs is a true oasis in the desert, patterned by nature and developed by man for his enjoyment and relaxation.

Charles: All of these families, who were pushed out of Section 14, which is now downtown Palm Springs, moved to the Desert Highland area or North Palm Springs.

Mr. Crossley bought these 20 acres or so because that was outside of Palm Springs city limits.

This was, at the time, outside of Palm Springs city limits.

And then everybody else went up to Banning, California.

Charles: And then over time... [Laughs] this became a part of the city of Palm Springs.

♪ ♪ ♪ J.R.: Palm Springs, like all of America, has a strong, bad history with racial issues.

But not every issue that's being claimed to be racially motivated is.

What happened 50 years ago I can't respond to.

You know, I don't know what happened.

So, that's why we wanted to look in further.

We asked our historical society, Is there any history on this neighborhood that we need to know about?

And that's when these pictures surfaced.

Renee: This came from a collection from a realtor who worked with a lot of developers.

His name was Philip Short.

And as I was digitizing all of his aerials, I'd never seen one with Crossley Tract or with municipal this-- this early.

I estimate it was late 1959, early 1960.

These trees were planted on all four sides of the municipal golf course.

So, I'm not sure whether all of these trees were planted when they designed the golf course, but I do know that as time went on, different developers bought all of the empty property around the golf course, and they would take down those trees so that their condominiums or whatever they were building would have golf club views.

Crossley Tract never took down the trees.

♪ Renee: I called The "Desert Sun."

Actually, I ran over there with the picture in hand and said, "Look," you know.

♪ J.R.: I'm surprised you don't know about this.

Sara: This is the first I've heard.

J.R.: Trae and them didn't tell you about these-- we found two pictures showing the trees being planted, or we have--we have--an aerial with nothing behind the trees.

And then there's another photo with either the trees being planted.

I think there's some picture with Lawrence Crossley.

There's a question on whether Lawrence Crossley planted them himself to separate the golf course from the neighborhood.

You tell me when you see the photos.

'Cause, you know, it casts a lot of doubt on that argument.

♪ J.R.: In fact, I think one of the pictures is with Lawrence Crossley holding a shovel, and I think what the--photo is, is the trees are there and they're all young.

So, he's either been planting the trees, they're unveiling the trees, or they're putting a shovel in the ground to break ground on the neighborhood.

But the trees were already there.

And there's an aerial showing them, as well.

That's why there's question about this.

♪ Jarvis: Apparently, in this--this photo, these are tamarisk trees that are there already.

Is that what the claim is, that the golf course was there and the trees were there before the homes were even being built?

Mina: That's the claim.

Mm-hmm.

No.

[Laughs] I don't agree.

I'm sorry.

You really can't tell what that is, uh, to be honest with you.

Kevin Williams: You wouldn't know those are tamarisks.

It's just a little scritch, scritch, scratchy.

Corinne: I don't think that the photos solve the problem.

Everyone's kind of gonna see what they want to see in them.

Um, and I--I personally don't think they prove anything, and I don't think they disprove anything.

I think they add to the conversation.

They're never gonna admit if it's racial, right?

They would never admit that.

But they have a history of racial activity.

It'd been great if they have documentation that Mr. Crossley planted those trees.

It'd been great if Mr. Crossley was still here to speak for himself.

And so, I don't buy that.

You're just trying to shift the blame.

I don't know what that is.

That looks like something-- I don't know what that is.

I know that when we were out there, we did not have trees around the golf--Crossley Tract.

There may not have been, um, as many Black residents as there are now on-- Crossley Tracts, but there were Black residents there before those trees.

You knew there was a housing development, and you knew Lawrence Crossley owned this land, and you knew he was building homes.

Hmm.

"Let's put these trees up now.

That way, we can keep them folks up out of there."

Mina: Oh, so you--you're actually saying that when you hung out in Crossley Tract, you do not remember any trees, like, in the late '50s.

Oh.

In the late-'50s, no.

Uh-uh.

There were not-- uh-uh.

Not trees.

I had a girlfriend out there, so I used to know her.

I said, "Oh, there's her house.

We're getting close."

[Laughs] So, no trees.

Tyrone: I don't know if it was a fact that the people who decided to plant those trees were racist, but it is a fact that people live with this legacy at the emotional and spiritual level for their whole lives.

They raised their families with the backdrop of those trees.

Tyrone: Racism isn't always provable, but you can bear witness to it.

It's not always explainable, but you know it in your heart.

♪ ♪ Janet Zappala: The so-called "racist trees" are back up for discussion once again.

The Palm Springs City Council voting tonight on whether to remove a line of tamarisk trees.

I don't know what it is about Palm Springs, but it seems like our minor issues, like nuisance trees, all of a sudden go international.

And, uh, you know, in this case, um, I think a lot of it is media hype.

One thing that's very, very clear, this was never a racial issue, this was never a segregation issue.

These trees were planted long before the houses were built.

Kevin Williams: It's deeper than the racist trees.

We know the past of the history of them, why they were there.

But, you know, at a certain point in life, it's like, when is it gonna change?

Mayor Robert Moon: Those trees have been there for 60 years, and they've just, frankly, become overgrown.

It's sho--really surprising to go in there and look at those trees.

I think most of us have.

Those trunks are four to six feet in diameter.

Councilmember: Whatever the motivation was for planting them in the first place, I can't imagine any responsible landscape architect that would ever plant trees in that kind of density that close to a property line.

Rosie: If you don't know about the past, then how can anything be better?

Because nothing happened to your family, but that doesn't mean it's not a human issue.

Councilmember: I think there have been a lot of alternative facts and misinformation about this issue.

No one from the city really said that this is a race--race issue.

Um, that was how it was portrayed in the media.

I know it went on Fox News, and we got a lot of emails right after that from people who don't even live in Palm Springs.

Um, but this is a nuisance issue.

Charles: We can't downplay what happened in history 'cause they'll tell you quickly, it's not racially motivated or, "We don't know anything about that."

OK, you're here now, so let's see what you do 'cause I'm paying attention.

Trae: Anything less than satisfying the neighborhood's request is subtle racism.

I'll just be blunt.

Mayor Moon: OK, we have a motion to approve made by Mayor Pro Tem Roberts and seconded by myself.

Motion is on the floor.

Tyrone: There are people in the town who don't believe that those trees were planted with racist intent.

But it almost doesn't matter what other people think of the trees.

It's, Do these Black people feel as if they belong in this town because these trees were planted?

Tyrone: We're not gonna get anywhere if we only talk about whether or not one person is a racist, but how institutions can be racist, how cities can be racist, how a system can be unjust even as there are good people operating it.

♪ Councilmember: Motion passes 5-0.

Mayor Moon: OK, Thank you.

I would suggest that we do come up with a release, waiver, form or whatever, and we provide it to the people who actually have owned the homes contiguous to the golf course.

And if someone doesn't want to sign it, we just won't remove the trees behind their house.

Corinne: All five city councilmembers voted in favor of taking out the trees.

I think part of it was, they saw, Yeah, this is--an issue that's really affecting people in our community, but then I think they also didn't want the negative attention.

Max Rodriguez: Take a good look at the trees behind me.

These are the trees in question.

But the City of Palm Springs say that after this week, these trees will be entirely gone.

[Excavator humming] ♪ ♪ Donald: But I felt like we were pushed into it.

If we didn't sign that paper, the trees would be left in right there.

And that's what--I was like, you know, do we wanna live the rest, you know, of our time here as the "ones" that--the racists on the street, you know, because we have the trees that are sitting in the back of our house that say, you're a racist, you know?

And it had nothing to do with it.

You know, for us, it had nothing to do with it.

It was security, you know, and protection.

That was it.

♪ ♪ [Exhales] Kevin Williams: This is the beautiful view I get now.

I feel like I'm Black and I'm part of Palm Springs.

[Laughs] It was very emotional.

At one point, I didn't think they would ever come out.

I've been playing in those trees and walking through those trees and told to get off that golf course plenty of times.

But to see them now gone brings a tear to my eye because I see change in Palm Springs.

Charles: Right about here, if you remember, we was only able to go because of the trees, um, being 60 feet high and about 10, 15 feet wide.

I'm able now to actually go all the way to the end of my property line.

But since the removal of the trees, not only am I still have the status of being on the golf course, I am a part of the golf course now, as well.

So, yeah, I love it.

I love it.

It's a brand-new day today.

[Laughs] So... ♪ Trae: I think it's gonna benefit the city.

It makes the city better, and it raises our consciousness level and makes everyone more aware of the fact that Palm Springs is not just a city of elderly White, LGBT individuals.

We are a multicultural, multiracial city.

And, uh, I think it's important to acknowledge that.

♪ Brooke Beare: A property owner in Palm Springs is raising safety concerns over blight visible from her tenant's unit.

It comes three months after controversial tamarisk trees were removed in the Crossley Tract neighborhood.

Direct view of the window here, uh, of the property.

So, uh, tenants that I have full time here now have this lovely view.

Reporter: Felando says while she didn't have an opinion on the tree removal at the time, but says other owners in her community were against it.

Kevin Williams: My neighbors across the way didn't want the trees out because of the way our neighborhood looked.

But it takes time and money, you know, to get to that point where we can fix up.

That was a stepping stone.

Kevin Harmon: A lot of people think people don't have generational wealth because of their own mismanagement of their life.

They don't think there are any outside things that might affect that other than them just being irresponsible and not figuring it out.

But it's more than that.

Whatever we have, they wanna take it from us and leave us with nothing.

We--we can't have our own anything.

So, we're gonna come in, we're gonna kill their economic status.

We're gonna stop them from owning homes.

Uh, we're gonna stop them from creating generational wealth.

Every house, every home that sits here should still be owned by that family.

[Jet engine whirring] Ray: Only two original family on this street out of probably, uh, 30.

To me, it's a sad thing, uh, what we have to go through in order to improve a better way of living.

Ray: People lose their homes.

People lose their neighbors.

And then when new people move in, they want the old people to change and adapt to their way of living.

[Ball hits backboard] [Indistinct chatter] Ray: And I know times change, but how are the young generation gonna survive?

[Kids laugh] Adriene: I think it made things better because those trees was raggedy, they were old.

And you felt like you couldn't breathe.

Yeah.

And you didn't know you couldn't breathe 'til the trees were gone, you know?

It's been there forever.

With these houses that they're building, they kind of shake you up a little bit, like, What's going on?

It's just a scary thing because-- We'll be pushed out.

Adriene: I think they're trying to just move in and take over and take our houses.

We get phone calls all the time asking do we wanna sell.

And I tell 'em, this is a generational family home.

Until it fall down, it's gonna be passed down, you know?

Different resident: That's right.

So, yeah.

Charles: Like, my parents, they worked hard, they bought three homes in this--this neighborhood.

They will not be sold, not as long as I'm living.

They're gonna remain in this family because that what White folks do.

And I hate to use-- refer to people as a color, and I think you should probably grasp that.

But I think that's why all this happens, is because we still don't look at each other as human beings and we don't realize that our mind-sets are different because of what happened, what, just a short hundred years ago and beyond.

'Cause it's not-- we're not that far removed from slavery, from it being "legal" to own other.

How do you own a human being, you know what I mean?

I mean, when you really think about it, how do you buy and sell another human being like they are a cow or a horse or a pig or a dog?

We're none of that.

We're human beings.

♪ Kevin Williams: Got some "Pizza!

Pizza!"

Bread sticks.

All right.

Thank you, Lord, for this food.

Amen.

Daughter: Amen.

With the nice view.

Yeah, it's beautiful.

It's like a giant backyard now.

Kevin Williams: Right.

It felt so small when--when it was up.

It felt closed in.

It felt closed in.

It felt so, like, closed in and small when they were up.

Kevin Williams: Now you feel like you're a part of something.

You're like, ahh, I'm in Palm Springs.

Daughter: Yeah, it's so nice to sit there and just watch the golfers.

I'll teach you how to golf, Chris.

♪ Callie: I'm so happy that Kevin did what he did, when he had the courage to continue, stick with it all the way, you know, so... so, now I get to have this view thankful-- thanks to my son.

As the kids were growing up, we always told them that they could have whatever they want, but they gonna have to work and make it happen, you know?

He did it.

So, and it's great.

So I look forward to whatever else is coming, you know?

So, it seem like it's a good life, you know?

[Laughs] You know, so... everyone should want to have a good life, you know, so... ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S25 Ep8 | 30s | Were trees intentionally planted to exclude and segregate a Black neighborhood? (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Indie Films

A diverse offering of independently produced films that showcase people, places, and topic

About Damn Time: The Dory Women Of Grand Canyon (2025)

Support for PBS provided by: